Anatomy of a Masterpiece, Paris (France) (2015)

Since March 10th to May 17th 2015 Quai Branly museum hosts in its space-atelier Martine Aublet Anatomy of a masterpiece, exhibition-installation that shows – through examples from the Museum’s collections – recent research and methods by means of digital instrumentation and non-invasive investigation techniques, to analyse the ethnographic object.

Since March 10th to May 17th 2015 Quai Branly museum hosts in its space-atelier Martine Aublet Anatomy of a masterpiece, exhibition-installation that shows – through examples from the Museum’s collections – recent research and methods by means of digital instrumentation and non-invasive investigation techniques, to analyse the ethnographic object.

History of non-intrusive study methods for the investigation of three-dimensional objects dates back more than a century ago, in 1896, with the first x-ray of an Egyptian Mummy, and steps forward in 1972 with the first x-ray scanners becoming available. However, today’s technology allows you to enter the subject, to see it from the inside, to virtually isolate its different components and ultimately to reconstruct 3D copies – all while keeping its integrity.

After a brief historical introduction to the multi-disciplinary subject, a first showcase houses a wooden anthropomorphic nkisi statue from Songye people (Congo), dated between 17° and 19° c. and – in rotation on the vertical axis on the surface of one of the crystal walls – its moving video image obtained from x-ray digital, where various internal components are highlighted from time to time. In this way you can simultaneously appreciate the object and its composition, which reveals an internal structure reproducing organs and processes necessary to life, and the insertion of metal objects in the openings (eyes, nose, mouth) and therefore visible, but also within the digestive tract – opening up the question of the reasons for this presence to block the potential flow of materials.

After a brief historical introduction to the multi-disciplinary subject, a first showcase houses a wooden anthropomorphic nkisi statue from Songye people (Congo), dated between 17° and 19° c. and – in rotation on the vertical axis on the surface of one of the crystal walls – its moving video image obtained from x-ray digital, where various internal components are highlighted from time to time. In this way you can simultaneously appreciate the object and its composition, which reveals an internal structure reproducing organs and processes necessary to life, and the insertion of metal objects in the openings (eyes, nose, mouth) and therefore visible, but also within the digestive tract – opening up the question of the reasons for this presence to block the potential flow of materials.

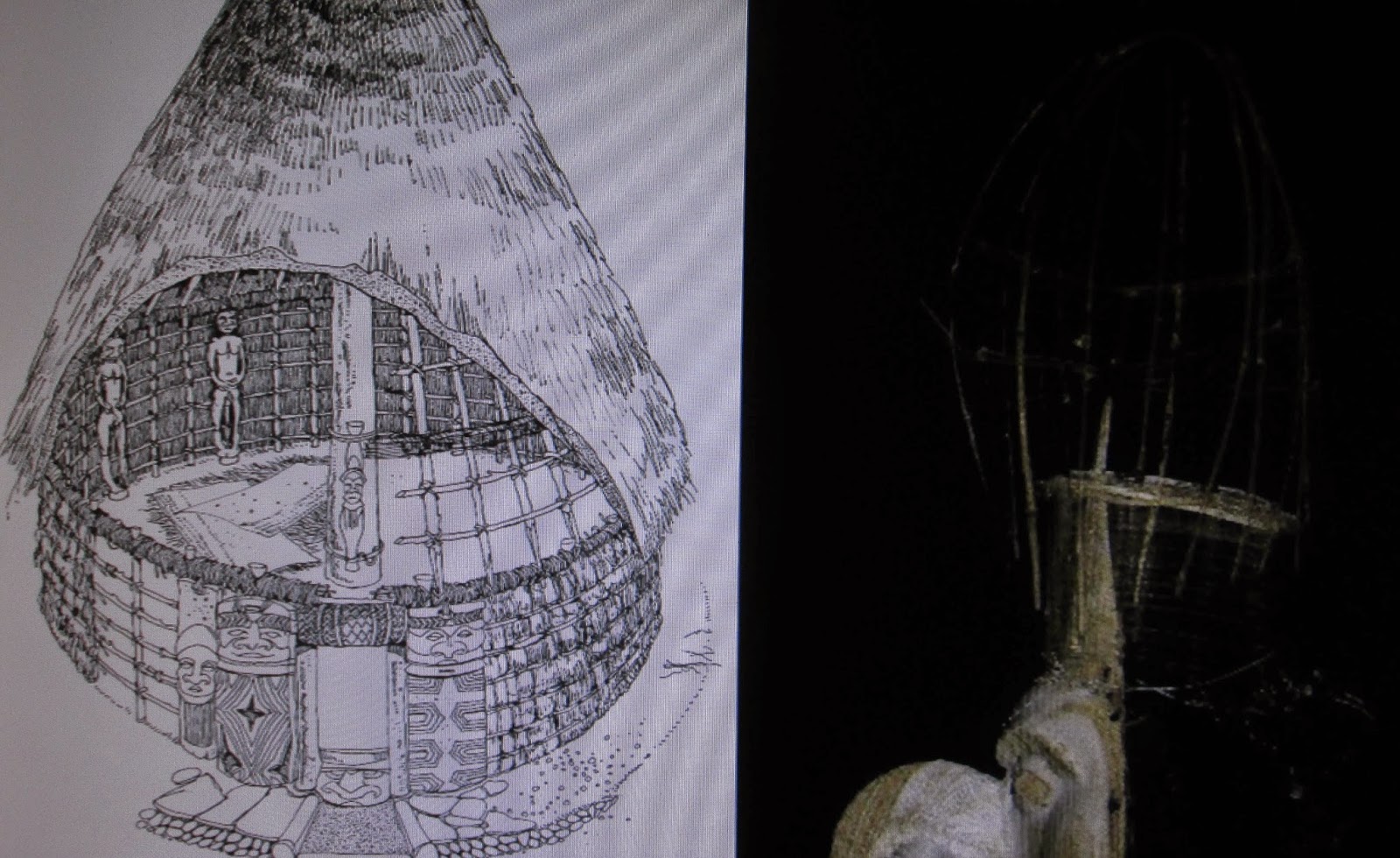

Next showcase illustrates the result of such techniques use for the investigation and restoration, in 2012, of twelve kanak masks (New Caledonia) again from the 19th century, one of which is here exhibited along with a video that chronicles the process of investigation and its findings. Here the analysis aimed at identifying ways to restore the object reinstating its original integrity through techniques as much as possible similar to original ones of production. But the x-ray scanning allowed an interesting discover: the inside of the mask top, where had later been applied hair and feathers, was actually made of a woven fibre structure that reproduced the same structure of kanak houses.

Digital current techniques can also envisage the collaboration of various professionals to research work on the same subject – especially when its composition or its functions are complex. Conservators, restorers, anthropologists, radiologists, anatomopathologists can for example make each one his contribution in the analysis of mummies, coffins and grave goods without having to act with dissections that would go along with not only the corruption of the object, but also with the potential risk of running into violations of cultural community (or its descendants) regulation on the object.

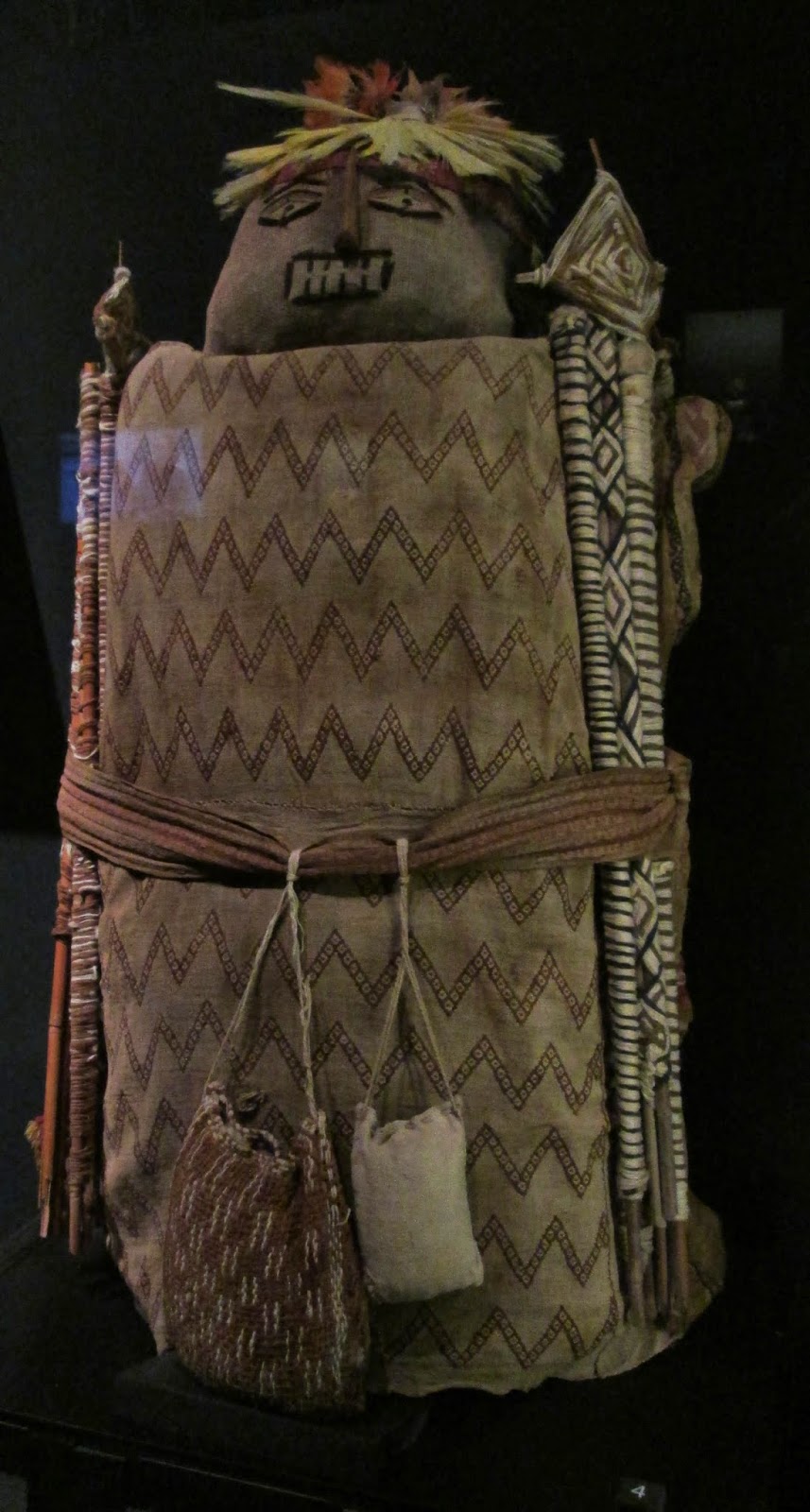

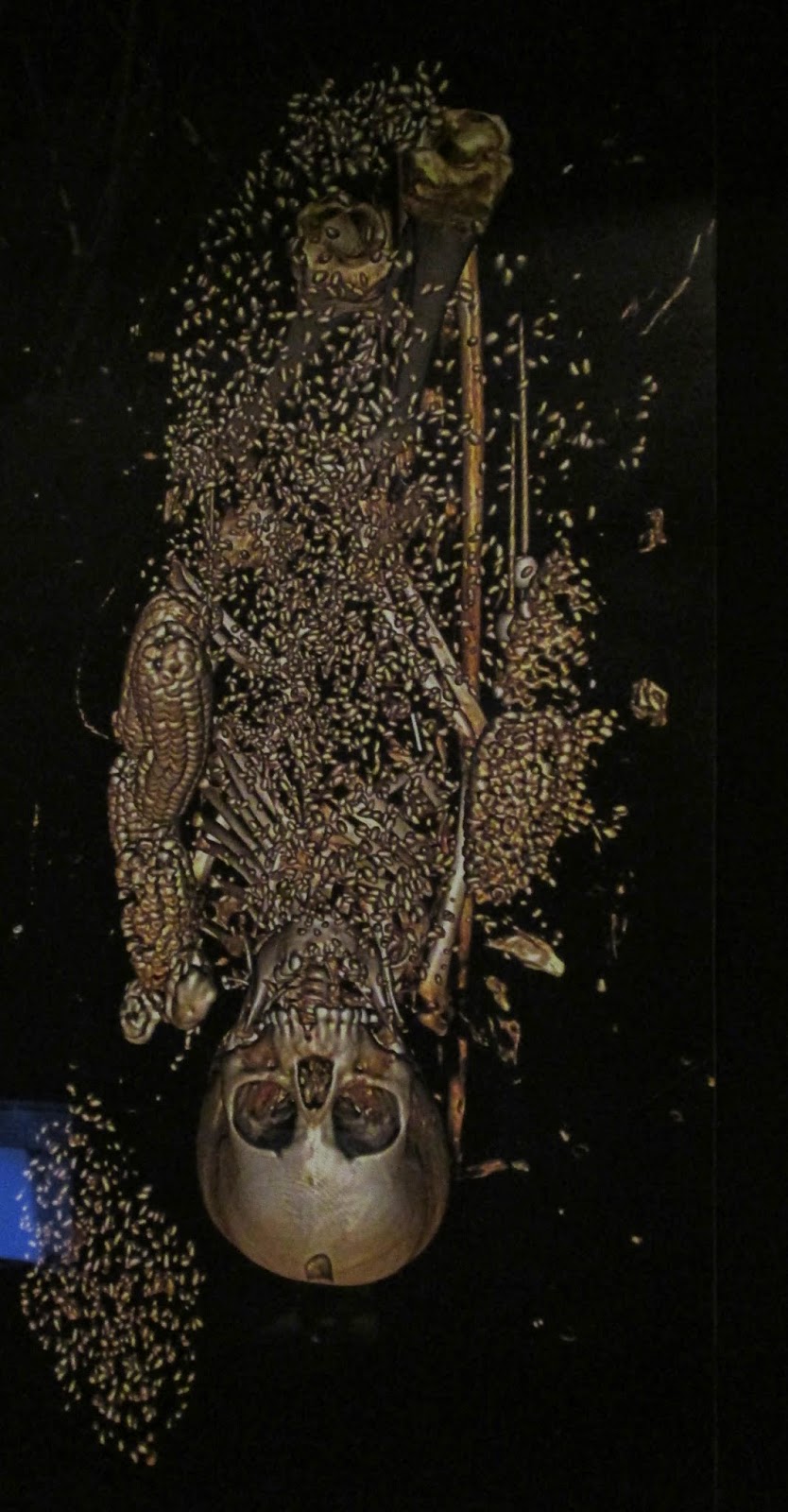

The case of a chancay (Peru) fardo – dating 1100-1450 – investigation illustrates such a collaboration: virtual analysis has revealed that the fardo is the mummy and funerary kit of a 5-6 years (as deduced from the development of the dentition and skeleton) child, whose causes of death are not identifiable in the absence of traumatic injuries. The body had undergone the removal of internal organs in order of its mummification and had been placed upside down in foetal position. The analysis of the skull – characterised by an accentuated dolichocephaly – revealed, however, that the same had been induced and, here was necessary the competence of other than the pathologist to understand that this deformation was a cultural tradition of the community at those times. Similarly, the presence of corn cobs on the sides of the body is explained by the concept of an afterlife that would require a ‘journey’, where ‘feeding’ could be equally necessary. The detailed investigation of the different components of the collection, as well as anatomical parts of the mummy, had then led to 3D prints, so that now these copies are observable without in any way touch the original, which can continue to give shelter to eternity to the child as his community planned.

The exhibition numbers numerous examples of the work that is done from time to time on magical-religious objects, headdresses, statues, especially when the coexistence of multiple materials in their production or their recognised complexity in operating may indicate an equal internal complexity invisible to the eye. Through the use of virtual scanning the internal accumulation characterising hoyo (Angola) and kongo (Congo) statuettes becomes visible: here, in fact, outside and inside a wooden anthropomorphic statue featuring several rooms, its creator puts ad hoc elements for the person or the effect interested by the work of the satue – overlapping and intertwined elements so that it would be impossible to identify them without physically dissecting the object and then making it lose his unity (and maybe its magical effect!).

The digital scanning tends therefore to provide information mostly related to the creation of the object, thereby indirectly to the understanding of its functions – issue however investigated by other disciplines. Still, it can happen that, sometimes, in revealing the production mode of the object, mysteries arise remaining unsolved.

Bizango statue of Port-au-Prince (Haiti), carried out by contemporary artist Lhérisson Dubreus, illustrates this case. Deposited by a voodoo temple before entering Quai Branly collection, the statue is an object belonging to bizango voodoo cult, about which anthropological literature knows very little as its followers maintain a degree of invisibility since generations, and same reticence on talking about cosmology and practices that characterize it. At its entrance in Museum’s collection in 2009, the statue was then scanned in order to understand its composition, and therefore hoping to getting – at least indirectly – some more information on the cult. However, the survey revealed an unexpected element: the presence of a Caribbean woman skull at the head of the statue, where the rest of the body is made of wood, metal, fabric and bits of mirrors at the mouth, ears, eyes.

Legitimate questions – whose was that skull?, how did she die?, where’s the rest of her body?, how did the artist get the skull?, why did he insert it into a statue? – at this point become pressing, although they remain unresolved, since their investigation and potential explanation goes beyond the objectives of the exhibition (not by chance hosted in a space-atelier aimed at staging temporary installations that question the relationship between anthropology and scientific disciplines, as well as between art and anthropology, as well as photography and post-colonial literature, in order to encourage or inspire ideas beyond the object itself and its ethnographic and historical contextualisation).

Similarly it is not out of place to point out once more that the ‘pop’ title “Anatomy of a masterpiece” of the exhibition may also open to an ‘exotic’ and ‘artistic’ imaginary, and therefore be of potential appeal to the public, but – by using the concept of “masterpiece” (subject of long-standing cultural criticism because of its ethnocentrism, as not rising the issues of who’s defining a masterpiece the cultural artefact and on the basis of which aesthetic criteria passed off as absolute) – the effect provoked on the specialists of the discipline is to irritate even the most indulgent among them by the clear evidence of words abuse and misleading meaning in the name of marketing strategies. Even when the same professional could give its approval for such a scientifically correct, well crafted and deeply informative initiative as Anatomy of a masterpiece is.

In conclusion, digital techniques and technologies of investigation are valuable to derive from an object and about the object ‘how’ it has been done through a non-invasive and non-destructive approach. This way, they also indirectly show a new caution and warning about the cultural context the object belongs. Nevertheless, the latest case shows that such practices are also take part to a number of unresolved ethical issues which are still under debate in the relationship between the different human cultures: the relationship visible-invisible in various contexts, legitimacy to unravel information in the name of knowledge that in some time are intentionally kept secret, the way of dealing with acquired knowledge and, ultimately, ethical limits of research.

No small thing when lives of individuals from different cultures inhabit all the same contemporaneity, and when we realise – last insight this exhibition points out – others strategies, like ours, try all to manage the same questions: life, its mystery and its critical phases like diseases and death.