Tatoueurs, tatoués, Paris (France) (2014)

From May 6th 2014 to October 18th 2015 the Quai Branly Museum in Paris hosts the exhibition “Tatoueurs, tatoués” which presents – in the words of its curators Anne and Julien, founders of the Group/magazine Hey! Modern art & pop culture – an overview of reasons, meanings and tattooing practices in contemporary world, and explains how the tattoo, from antiquity to the present day, has never stopped changing, disappearing, being born again according to collective or individual instances until becoming a fashion or, conversely, a hallmark of a personal unique identity.

|

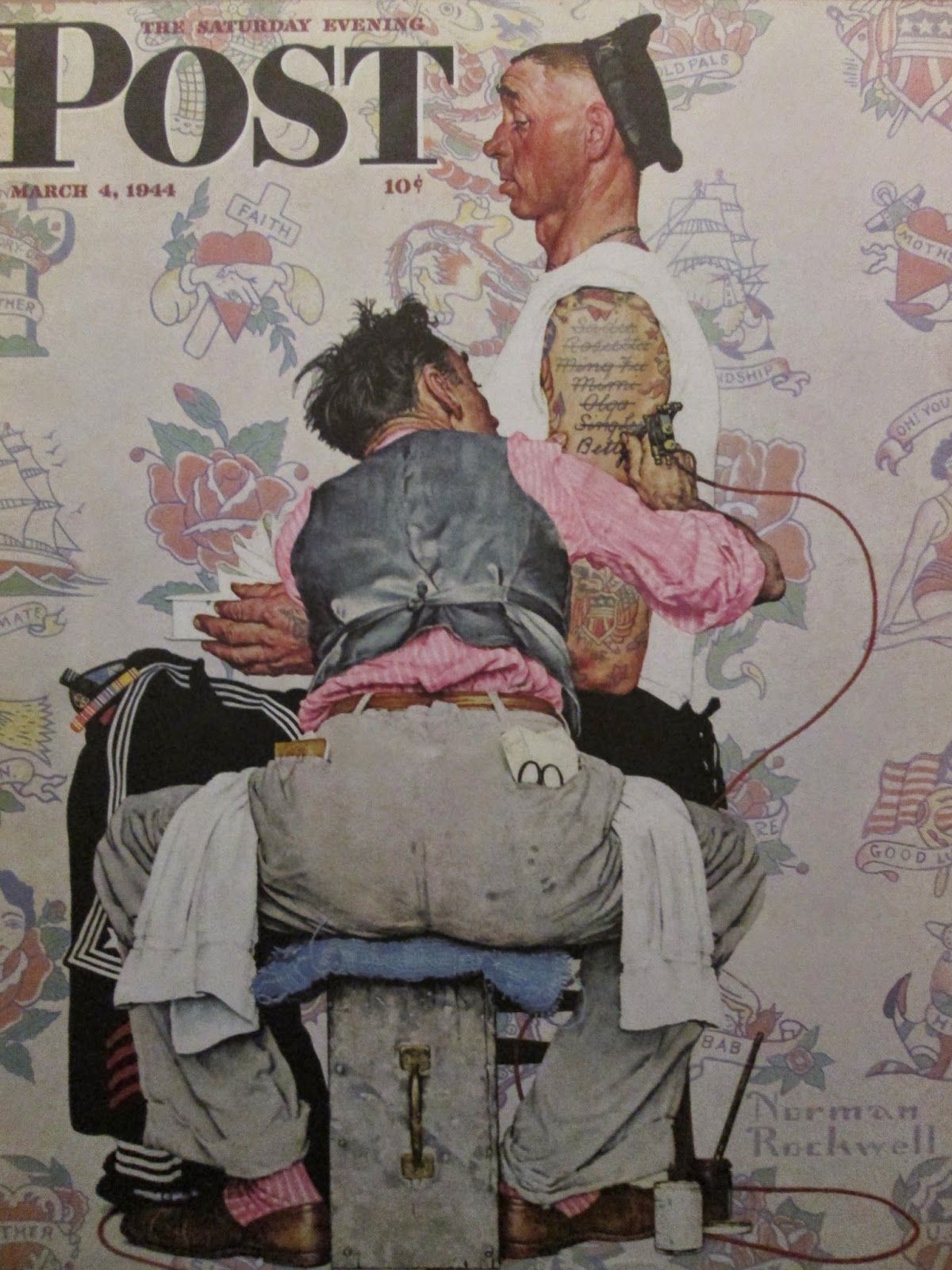

| “Tattoo Artist”, Norman Rockwell, USA, March, 4th 1944, reproduction of the cover of the Saturday Evening Post. |

Speaking in very general terms, in fact, in the far East, Africa and Oceania the practice had, until in the last century, peculiar social, mystical or religious meanings, and often accompanied the individual in achieving a certain status within the community, while in the West the tattoo was seen as a stigma related to crime world, or as circus attraction. However, during the 20th century we verify a substantial change in European and North American world, so that this practice exits from original marginal circuits to become increasingly frequent in different urban contexts not marking anymore the individual as a ‘deviant from the norm’. Not to mention these last years, when tattooing becomes even a pure ornament.

|

| “The tattooist”, Anonymous, Italy, 17th century. |

Next to treat the topic in these terms – well apart from an ethnographic exhibition on the theme that otherwise would widen its meanings in various human cultures in relation to various components and worlds vision by a community – the exhibition emphasises the artistic nature of this practice, the exchange of expertise among tattooists in the world and the current emergence of syncretic styles. The aim to develop a representation embracing both a documentary and aesthetic perspective is made effective by freely mixing cultural artifacts held in the museum as well as sketches, photographs, and sculptures made ad hoc by contemporary practitioners of this art.

|

| Myanmar’s manuscript manual of the 19th century. |

Here we find interesting materials, such as a Myanmar’s manuscript manual of the 19th century in which are magical beliefs-tattoos and their associated religious and that it was in fact the Clipboard – intended for destruction at a time when he had become a professional, a master student of art. They are also collected numerous images of tattooed women, often to identify them as prostitutes (as in the case of the Armenian genocide has already escaped, but not slavery, in the 20’s in Syria) or by their own choice to become a circus attractions (as in the case of Anna Artoria Gibbons).

|

| Jessie Knight tattooing a custumer, UK, 1955. |

A second section explains the roots of the practice in Japan (where initially used for punitive reasons, then military, then reaching its peak in the ornamental function coinciding with the period of greatest success of ukiyo-e, where the style and the subjects are linked), in North America (where it is found sporadically in some native populations, but especially where after the second half of 19th century it begins to spread in the urban context – and here we can see a reproduction of the same 1981 patent with which Samuel O’Reilly recorded the first electric tattoo machine), and finally in Europe (where it develops since the 19th century and where in 1936 Jessie Knight, which advertises herself as the first and best artist of the time in freehand work, opens her shop whose customers are women from different social extraction, here photographed while they scream or smile during the tattoo).

A third section discusses tattoo revival in those societies where it is/was in connection with rites of passage and specific status within a community – New Zealand, Samoa, Polynesia, Borneo, Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand – checking the ways in which the contact with the Western world has led to the emergence of ‘schools’, ‘professionals’ and meanings sometimes in agreement (as in the case of New Zealand businessman dressed in impeccably Western way, but with his face entirely covered by a design of their own culture), sometimes at odds with the traditional reasons. A fourth section deals with the area of China, where the practice is also re-emerging, and latino and chicano context, where the tattoo is inspired by the American-Mexican iconography that includes Christian pantheon and funerary images.

A third section discusses tattoo revival in those societies where it is/was in connection with rites of passage and specific status within a community – New Zealand, Samoa, Polynesia, Borneo, Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand – checking the ways in which the contact with the Western world has led to the emergence of ‘schools’, ‘professionals’ and meanings sometimes in agreement (as in the case of New Zealand businessman dressed in impeccably Western way, but with his face entirely covered by a design of their own culture), sometimes at odds with the traditional reasons. A fourth section deals with the area of China, where the practice is also re-emerging, and latino and chicano context, where the tattoo is inspired by the American-Mexican iconography that includes Christian pantheon and funerary images.

|

| A tattoo by Yann Black (2013). |

A fifth section, finally, deals with the issue of new ornamental styles illustrated by the images of eight specialized photographers on the subject, and the screening of a video illustrating the social trends and fashions that they invest it. The latter proposal takes over and closes the exposure of 13 parallel imaginary projects, by many current tattooists, on arms, legs and torsos made of silicone, and 19 canvases painted with subjects for tattoos from the same practitioners of the art.

Purely aesthetic and spectacular, this last section paradoxically seems to be the least effective, judging from the boredom by visitors. As an anthropologist, I would be and am somewhat perplexed mainly about this last part too, but I recognise “Tatoueurs, tatoués” has undoubted the merit of treating a well documented and peasant overview on the topic without the morbidity that often accompanies the discourses on the body and individual choices on its permanent modifications, as well as to stage the presence of women as well as men’s. No small thing if we put in relation the words “body modification” and “women” in our minds and see what comes…